The ribbon candy arrives every December in a decrepit orange VW bug, swirls of radioactive corn syrup contorted into impossibly long curlicues, one infinity symbol stacked atop another. The candy is hard, hard enough to cut your gums. You’re supposed to suck on it and this simply doesn’t work for me. I know I’m expected to love it, to love the effort behind it, not only the effort of our friend Shari for procuring it, but the effort of the people who formed those impossibly long curlicues. The truth is, I don’t love it. The flavors taste artificial. My tongue balks at the yellow #5 and red #3. Maybe my parents hate the ribbons too, and dump the candy in the backyard for the squirrels to use as the skeleton for their nests.

In those days, we could only recycle aluminum cans. I remember throwing thirty or forty cans down the back stairs and racing to stomp them on the cement floor of the basement. The ribbon candy arrives in an aluminum rectangle, maybe five by seven. The top, surely #6 plastic, tucks securely into the edges of the aluminum.

I don’t know how the ribbon candy tradition started. Maybe the same way the Shari tradition started. She always arrives in an orange VW bug. She wears a sweatshirt adorned with cat fur. Her thick hair, auburn in color and flecked with gray, is parted on the side and curled under at the ends, a tribute to the late ’60s.

She once taught English. Now she works at Northwest Orient Airlines. Something happened and as I grow I glean more of the story. Shari fell in love with a married man, they were soulmates, he promised they would be together. Did he live in Minnesota? No, I imagine him on the East Coast, tucked into his comfortable family, breaking the heart of our friend.

On one particular visit, I’m standing behind the wingback chair in the living room, facing the windows, listening to Shari and my dad in the heated midst of a pun battle. And I suddenly experience my own little epiphany – I understand puns for the first time! My dad is proud. This is the true Lippin rite of passage. Mom tolerates puns but rarely partakes. She is a Milanese masquerading as a Lippin.

Dad and Shari speak German when they aren’t speaking puns. When they’re feeling particularly feisty they pun in German. Shari refers to my dad as “du,” even in the midst of normal conversation, her version of “hun” or “love.” Her funny vocal mannerisms, the “du” and a little hum that she inserts into blank moments, leave me with the impression that Shari is lonely and I feel a tentative sadness for her in my childish brain.

Shari and her sister haven’t spoken in years. As an only child, this makes no sense to me. If I had a sister, I naively vow, I would never let anything or anyone come between us. Her mother lives in a huge house by the lakes. We go over to help clean out the house after the mother dies. Few tears, if any, are shed. We never visit Shari’s apartment. She never invites us.

I’m away, maybe at college, maybe home afterwards while I finish pre-med. But still away in the way of a young adult, self-focussed and flip. My mom describes Shari’s apartment, a tiny studio off Grand Avenue in Saint Paul, the piles of books, the cat hair, the garbage scattered on the floor, the lack of air. Shari is a hoarder before the word exists. With a lack of research and vocabulary, we struggle to understand. Does she have OCD? Did her love trauma predispose her to this hell? Is she somehow related to Grandma Lima? My aunt and my mom methodically help Shari clean out the apartment. Then they move on to the storage units, jam packed with cookbooks and bolts of baby fabric, duckies and bunnies and rainbows.

Shari won’t seek help, afraid she’ll lose her insurance or even her job. Shame rolls like toxic gas under every interaction.

The phone rings one day, I think it’s spring or summer. My parents aren’t home. I answer. Hello, is this? No, I’m her daughter. We don’t usually give news like this over the phone, but your dad is listed as the power of attorney.

Shari is dead.

Her beloved cat is missing, escaped through an open window. My dad goes on a feline rescue mission and finds a cat that fits the description. He captures the cat, a thrill of success in an otherwise dismal situation. In an ironic twist likely orchestrated by Shari herself from some celestial plane, the real cat turns up in the apartment. Dad returns the abductee to the neighborhood.

Her memorial service is tan in my memory, a flat tan room devoid of vibrance, lacking the quirkiness that characterized the living Shari. The daughters of her friends weep. We, the surrogate children, weep. The other girls wear the JB Hudson cultured pearl earrings bestowed upon them by Shari on the occasion of high school graduation. Shari and I went shopping at Hudson’s together, searching for a similarly-priced substitute since my earlobes were intact. I wore the thin gold band on my left middle finger for years.

The contents of Shari’s apartment scatter to the various kids. Molly gets the white bookcases. Ethan takes possession of the orange VW bug. My mom thinks the bug went to the junkyard and not to Ethan. I remember him driving it though, watching the road through the holes in the floor.

I take a few cookbooks, glossy and pristine. Somehow I wind up with a handful of silver jewelry, evidence of Shari’s travels, her life before the mental illness derail.

Does her ghost still hang in that apartment half a mile from my house, trapped by regret, unable to move beyond?

Now that we know, now that we can name and diagnose, the past falls into a bleak focus. Why didn’t someone drag her to the doctor? Did we kill Shari by helping her clean out her home, by removing her chaotic pit of safety? If only this had played out ten years later, when SSRIs had a long track record and people were more comfortable discussing mental illness. If only.

I imagine the bolts of baby fabric, converted to onesies and quilts, comforting generations of children. I wear the jewelry, connecting to the one from whom it came. And when I see ribbon candy, I remember.

Musical Moment

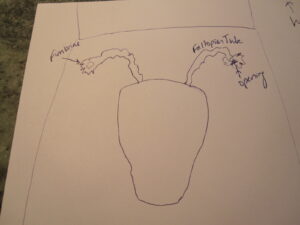

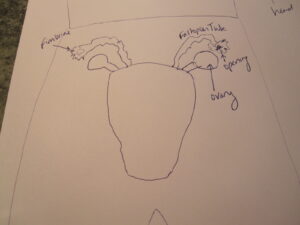

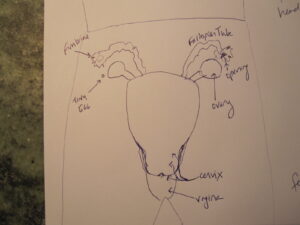

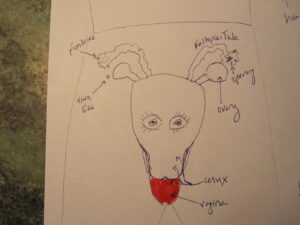

Now we’ll add Rudolph’s head – the uterus.

Now we’ll add Rudolph’s head – the uterus.

At the ends of the antlers are fimbriae – or fingers – that wave like a sea anemone.

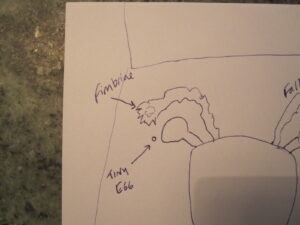

At the ends of the antlers are fimbriae – or fingers – that wave like a sea anemone. In a woman or girl who gets her period, an ovary spits out an egg once a month (ovulation; like a jelly bean falling out of Rudolph’s ear).

In a woman or girl who gets her period, an ovary spits out an egg once a month (ovulation; like a jelly bean falling out of Rudolph’s ear).  The fimbriae of the adjacent fallopian tube wave and try to lure the egg into the tube. The ovaries alternate months – the right ovary contributes an egg one month and the left ovary the next month.

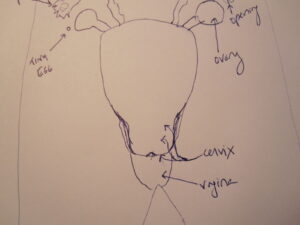

The fimbriae of the adjacent fallopian tube wave and try to lure the egg into the tube. The ovaries alternate months – the right ovary contributes an egg one month and the left ovary the next month. The opening of the cervix is visible inside the vagina. Think of the vagina as Rudolph’s nose. If it’s red, think yeast infection.

The opening of the cervix is visible inside the vagina. Think of the vagina as Rudolph’s nose. If it’s red, think yeast infection.  Ouch.

Ouch.

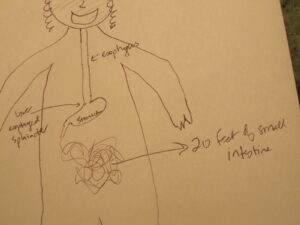

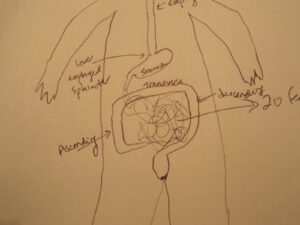

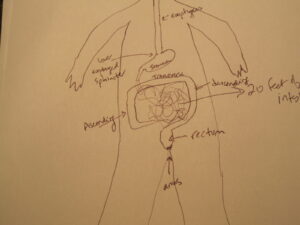

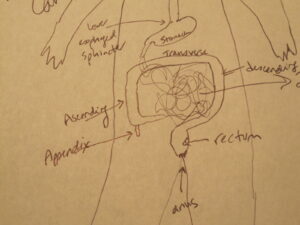

After banging around in the stomach for awhile, the food passes into about twenty feet of small intestine. In case you’re wondering, the small intestine is divided into three parts: the duodenum the jejunum and the ileum.

After banging around in the stomach for awhile, the food passes into about twenty feet of small intestine. In case you’re wondering, the small intestine is divided into three parts: the duodenum the jejunum and the ileum.