I read a piece in the Washington Post this week: “Parenting as a Gen Xer: We’re the first generation of parents in the age of iEverything.” Frankly I’m perturbed, always a tenuous platform from which to write.

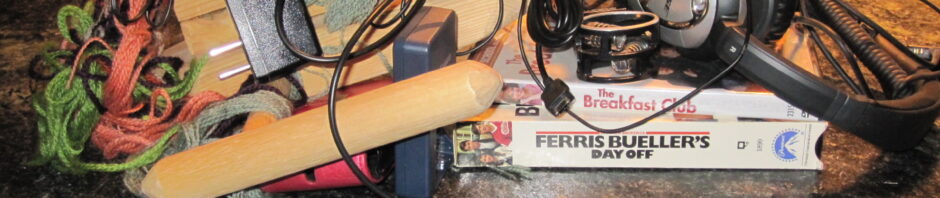

I, too, am parenting (and childing) as a Gen Xer. I helped my mother fix her Facebook privacy settings. I contacted my son’s school to inquire how much screen time to expect in a fourth grade classroom. I ran through all possible permutations of passwords, trying to help Mom get back into her email account. I look across the headphones and iPhones and iPads and smartwatches and I, like Wash Post author Allison Slater Tate, wonder if awkward John Hughes moments are even possible anymore.

Here’s what I want to say and I’ll make every attempt at diplomacy, because as we all know: Once Posted, Always Posted.

Slater Tate says, “What we are doing is unprecedented,” referring to parenting kids in a techie society. What we do as parents is always unprecedented in our ever-evolving world. Raising children in a community with a safe water supply and enclosed sewer system. Public educational standards in constant flux. Parenting in 1960, the year The Pill became available. The advent of antibiotics and vaccines.

Imagine the profound impact of the automobile on parenting. The car is the single most life-threatening gadget to which we, in the US, expose our children, most of us daily.

So what’s different? Why is technology the “trickiest parenting challenge” Slater Tate faces? I argue that the tricky part is not inherent to technology but to the parent. We, as parents, finally realize that we can’t necessarily trust Nestle and Joe Camel, Pfizer and Disney with the best interests of our children. Ignorance isn’t bliss. We sift through the 650,942 Google answers to various parenting questions, on an endless quest for The Truth. Give me a yes or a no! Will thirty minutes of Call of Duty per day produce any longstanding detrimental effects on my teenager?! Does texting damage interpersonal interaction? Is reading online equivalent to reading an actual book? Does websurfing diminish the capacity for undivided, deep attention?

The Truth is hard to find, and as Slater Tate states, we won’t know the long-term impact of these novel techie childhoods for decades.

Life in our technologically-driven time means that whatever decisions we make can be shared with and judged by countless other humans, both friends and foes. When we dangle our baby over the edge of a balcony or outfit her with a faux suicide bomber vest (so adorable (it’s sarcasm, folks)), the world can post its vitriolic, virtually anonymous opinions almost instantaneously. When we breastfeed in public, take silly videos of our kids in various states of dress and undress, and discipline our children, people feel entitled to judge us according to their own culture and morals and upbringing.

I’m not saying that any of the above is an example of good, bad, or sideways parenting. I’m saying that no matter what you do, people will judge you. And the excess of immediately-available information, no matter the veracity, often makes people feel like they know better, and so should you.

Most parents in the US are striving to raise healthy, kind, competent children. Even this is an unprecedented shift, relatively speaking. The concept of Child as inherently valuable with an independent intellectual and emotional life worthy of study is radical in the grand scheme of civilization.

Good for us! Now that we value our children, we wade through the glut of websites, ebooks, and blogs, trying to do the best we can.

We are not passive recipients in life. Technology doesn’t happen to us. We create it. We control it.

Let me respectfully suggest the following approach to Allison Slater Tate: Gather information. Weigh the risks and benefits. Make an informed decision. And then OWN IT. “This is the choice we made for our family.” If you’re uncomfortable, revisit the steps. Gather more information, weigh pros and cons, and make another informed decision.

I appreciate and share (empathically, not technologically) your ambivalence and discomfort. You’re doing the best you can – thank you.